Why West Virginia and the nation must confront the quiet crisis of PTSD among those who serve

The sound of a siren is something most of us hear in passing. We pause, move to the side of the road, and then continue on with our day. For those on the other end of that sound, life pauses in a different way. Every tone, every call, every voice on the radio carries the weight of someone’s worst moment.

These are the men and women who hold the line when the world tilts, who walk into chaos so that others can stand on solid ground again. Their courage is often celebrated, but their quiet suffering is too often overlooked.

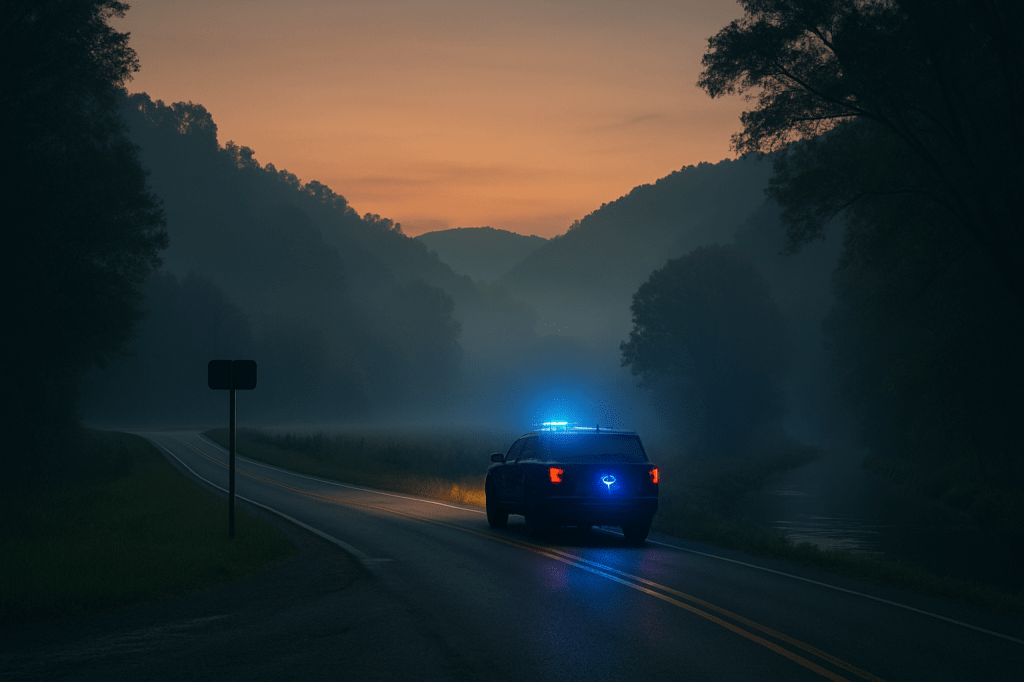

Long after the sirens fade, the echoes stay. Post-traumatic stress does not always shout. Sometimes it whispers in the quiet after a call, in the space between sirens and sunrise. It hides behind small talk in the break room, behind steady hands gripping a steering wheel on a dark back road, or behind a calm voice in the dispatch center that carries someone else’s panic without ever showing its own.

I have lived my entire life behind the thin blue line. I have loved, supported, and interacted with countless first responders, and I have seen firsthand the toll this calling can take on a person’s heart. The weight of what they see does not stay at the scene. It follows them home, tucked behind the tired smile at the dinner table or in the silence that lingers long after the radio goes quiet. That weight is not only emotional; it is physical, spiritual, and generational. Too many families behind the line quietly carry it.

Those who wear the uniform, officers, medics, firefighters, and dispatchers, see both the heartbreak and the holiness of this world, sometimes in the same hour. They step into chaos so the rest of us can stay safe, then drive home beneath the same stars we do, trying to find their way back to ordinary life. The memories do not always stay where they are supposed to. They follow like shadows across the hollers, like echoes that linger in the valley long after the noise fades.

For dispatchers, the trauma often lives in what they cannot see, the voice that goes silent, the call that ends too soon. Research published in the Journal of Traumatic Stress found that even without physical proximity to danger, emergency telecommunicators experience duty-related trauma comparable to on-scene responders.

A 2025 meta-analysis in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology estimated that about 14 percent of active first responders experience probable PTSD symptoms during routine duty, while 8 percent develop it after critical incidents. Other studies show that about 11 percent of dispatchers meet clinical criteria for PTSD, and some national surveys place that number closer to one in five. The message is clear: the voice behind the call carries a heavy burden.

Some advocacy groups, including the Ruderman Family Foundation, have reported years when firefighter and police suicides outnumbered line-of-duty deaths. The numbers shift from year to year, but the pattern points to one truth: the emotional toll of service can be fatal when left untreated.

Real strength is not quiet suffering. Healing begins when truth finds a voice. Departments, communities, and state leaders should treat mental health like any other piece of life-saving equipment, something essential, maintained, and trusted. Research from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has shown that consistent access to peer support, trauma-informed counseling, and chaplain care reduces long-term stress injuries across EMS and 911 workforces.

Here in West Virginia, progress has begun. In 2021, the Legislature recognized post-traumatic stress disorder as an occupational hazard for first responders under §23-4-1f of the state code. The law allows PTSD to be considered a compensable occupational disease if certain criteria are met and the employer elects to provide coverage. The statute includes law enforcement officers, firefighters, EMTs, paramedics, and emergency dispatchers, acknowledging what those in uniform have long known: trauma does not end when the call clears.

In 2025, House Bill 2797 expanded that protection by allowing certified mental health nurse practitioners and psychiatric physician assistants to diagnose PTSD under specific qualifications. The bill also removed the sunset clause, making the law permanent and widening access to care.

Beyond our borders, other states are answering the same call. Pennsylvania’s Act 121 of 2024 made it easier for first responders to receive workers’ compensation for PTSD, recognizing that trauma can result from a single event or years of cumulative exposure. In New York, the First Responder Peer Support Program Act established confidential peer-to-peer networks to help responders process trauma early. Mississippi created a First Responder PTSD and Suicide Prevention Task Force, and nearly 30 states now include some form of mental health coverage or protection for first responders under their workers’ compensation laws.

What all these efforts remind us is simple: this is not about politics; it is about people who spend their lives answering someone else’s call for help. Now it is time we answer theirs. Expanding telehealth, funding regional chaplain programs, and closing the coverage gaps that still exist in employer-elected systems are more than policy choices. They are moral ones.

When we honor the badge, the turnout gear, the medic’s bag, or the headset in the dim glow of a dispatch center, we must also honor the person beneath it, the one who has walked through fire, or listened to it burn, and still shows up. The stories they carry are heavy. No one should have to shoulder them alone.

PTSD does not mean broken. It means human. And sometimes the bravest thing a first responder, or the voice behind the call, can do is not to run toward danger, but to admit when the smoke of it still hangs in their chest, waiting for light to break through the hills.

Leave a comment